Farewell to 2012, and a Happy New Year to all our readers for 2013. Here's a stylish radio drama for the turning of the year, based on a classic weird tale from Russian literature. And the moral of the story is - do not wager anything on the turn of a card. As if you would.

Monday 31 December 2012

Friday 28 December 2012

'The Haunted Dolls' House'

The Haunted Dolls House from Stephen Gray on Vimeo.

Excellent zero-budget adaptation of a classic. Check out Stephen Gray's M.R. James site.

Excellent zero-budget adaptation of a classic. Check out Stephen Gray's M.R. James site.

Thursday 27 December 2012

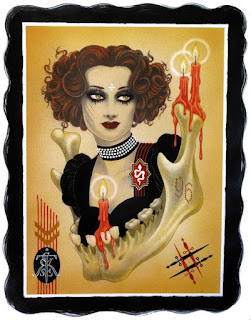

Nights of the Round Table

The Christmas season is traditionally a time for tales of the supernatural, and this year I took advantage of some time away from the distractions of blogging and Facebookery to re-read one of the true classics of the genre. Margery Lawrence came to prominence in the decade after the Great War as an author of shorts stories, most of them weird or ghostly in nature. Her first collection, Nights of the Round Table, was reprinted in the Nineties by Ash-Tree Press in 1998. Richard Dalby edited and introduced the volume, heaping praise upon Lawrence for the diversity and originality of her work.

The dozen stories in the collection purport to be those told to the author by members of a select club that meets once a month. Thus January's tale is the first to be told, while December's is the last. Lawrence is in fact a bit erratic about the introductory matter, offering quite a build-up in some cases, while in others she plunges straight into the narrative. There's a slight touch of the John Silence about this, and indeed Lawrence was a convinced believer in the occult and attended many seances. However, unlike many spiritualists, she doesn't let her imagine limit itself to bland statements about the nature of the life to come.

Far from it. One of Lawrence's notable achievements in NotRT is to give a well-defined but still alarming picture of a supernatural world adjacent to ours, from which various disturbing entities may intrude from time to time. Thus in 'The Fifteenth Green', the construction of a new golf course necessitates the eviction of an eccentric old man living in an unlicensed shack. The old man, predictably enough, has had dealings with unholy beings. But the way in which Lawrence builds up from the initial dispute to the final scene of vengeance is a masterpiece of careful storytelling. She perfectly captures the way 'sensible chaps' wouldn't allow some odd occurrences put them off a round of golf - despite all the signs that they are heading for catastrophe at the eponymous hole.

Likewise 'The Woozle', a story in which a nursemaid invents a monster to keep a lonely child quiet, works as a clever evocation of the cruel mind-games adults often unwittingly play with the young. But it's also an original take on the idea of the dark entity that is summoned by human fear and credulity - if you believe in it, it will come. A similar idea, but one executed very differently, lies at the heart of 'Floris and the Soldan's Daughter', in which an unworldly law student becomes obsessed with a beautiful ivory figure. While 'The Woozle' resembles Wakefield's fiction in its focus on casual cruelty, 'Floris' has hints of Blackwood and Machen, particularly in the denouement, when it's not clear whether Floris has suffered a terrible or a wondrous fate. Perhaps he has earned both.

'Vlasto's Doll', by contrast, is somewhat Grand Guignol in its emphasis on abuse, revenge, and the evil shenanigans of a ruthless showman. The doll of the title is a larger-than-life thing apparently moved by some internal mechanism. But why is Vlasto's wife, whom he mistreats brutally, so essential to the working of an act she apparently takes no part in? Here the climax of the story is nightmarish, perhaps appropriately, given that the setting is Europe on the brink of the First World War. If so the doll, with its apparently scientific mechanism driven by fear and hate, might stand as a image of greater forces of destruction.

'The Haunted Saucepan' sounds absurd, but in fact it's a fine story and has rightly been anthologised more than once. The premise is simple enough - something bad happened in a London flat, and it is connected with a saucepan that seems to boil and bubble despite being empty on an unlit stove. The backstory is not especially original, but the execution is extremely good; Rosemary Pardoe has describe it as a story in best Jamesian tradition.

Slightly less effective, but still very good, are 'Death Valley' and 'The Curse of the Stillborn'. In both cases the theme is the collision of Western values with those of older, stranger cultures. In 'Death Valley' a group of white hunters insist on exploring an area shunned by natives, and encounter a nightmarish entity - perhaps a demon - in an abandoned farmstead. The others story is set in Egypt, and concerns a very believable instance of missionaries seeking to put down 'native superstition'. Instead the intruders encounter something more ancient than the pyramids - a thing bound in the wrappings of the tomb, and wearing a gilded mask...

Those are just some of the stories in a collection that offered me a satisfying bedtime read over the past few days. Nights of the Round Table is not easy to get hold of, but according to Ash-Tree's web site some copies are still available.

The dozen stories in the collection purport to be those told to the author by members of a select club that meets once a month. Thus January's tale is the first to be told, while December's is the last. Lawrence is in fact a bit erratic about the introductory matter, offering quite a build-up in some cases, while in others she plunges straight into the narrative. There's a slight touch of the John Silence about this, and indeed Lawrence was a convinced believer in the occult and attended many seances. However, unlike many spiritualists, she doesn't let her imagine limit itself to bland statements about the nature of the life to come.

Far from it. One of Lawrence's notable achievements in NotRT is to give a well-defined but still alarming picture of a supernatural world adjacent to ours, from which various disturbing entities may intrude from time to time. Thus in 'The Fifteenth Green', the construction of a new golf course necessitates the eviction of an eccentric old man living in an unlicensed shack. The old man, predictably enough, has had dealings with unholy beings. But the way in which Lawrence builds up from the initial dispute to the final scene of vengeance is a masterpiece of careful storytelling. She perfectly captures the way 'sensible chaps' wouldn't allow some odd occurrences put them off a round of golf - despite all the signs that they are heading for catastrophe at the eponymous hole.

Likewise 'The Woozle', a story in which a nursemaid invents a monster to keep a lonely child quiet, works as a clever evocation of the cruel mind-games adults often unwittingly play with the young. But it's also an original take on the idea of the dark entity that is summoned by human fear and credulity - if you believe in it, it will come. A similar idea, but one executed very differently, lies at the heart of 'Floris and the Soldan's Daughter', in which an unworldly law student becomes obsessed with a beautiful ivory figure. While 'The Woozle' resembles Wakefield's fiction in its focus on casual cruelty, 'Floris' has hints of Blackwood and Machen, particularly in the denouement, when it's not clear whether Floris has suffered a terrible or a wondrous fate. Perhaps he has earned both.

'Vlasto's Doll', by contrast, is somewhat Grand Guignol in its emphasis on abuse, revenge, and the evil shenanigans of a ruthless showman. The doll of the title is a larger-than-life thing apparently moved by some internal mechanism. But why is Vlasto's wife, whom he mistreats brutally, so essential to the working of an act she apparently takes no part in? Here the climax of the story is nightmarish, perhaps appropriately, given that the setting is Europe on the brink of the First World War. If so the doll, with its apparently scientific mechanism driven by fear and hate, might stand as a image of greater forces of destruction.

'The Haunted Saucepan' sounds absurd, but in fact it's a fine story and has rightly been anthologised more than once. The premise is simple enough - something bad happened in a London flat, and it is connected with a saucepan that seems to boil and bubble despite being empty on an unlit stove. The backstory is not especially original, but the execution is extremely good; Rosemary Pardoe has describe it as a story in best Jamesian tradition.

Slightly less effective, but still very good, are 'Death Valley' and 'The Curse of the Stillborn'. In both cases the theme is the collision of Western values with those of older, stranger cultures. In 'Death Valley' a group of white hunters insist on exploring an area shunned by natives, and encounter a nightmarish entity - perhaps a demon - in an abandoned farmstead. The others story is set in Egypt, and concerns a very believable instance of missionaries seeking to put down 'native superstition'. Instead the intruders encounter something more ancient than the pyramids - a thing bound in the wrappings of the tomb, and wearing a gilded mask...

Those are just some of the stories in a collection that offered me a satisfying bedtime read over the past few days. Nights of the Round Table is not easy to get hold of, but according to Ash-Tree's web site some copies are still available.

Monday 24 December 2012

Saturday 22 December 2012

Wednesday 19 December 2012

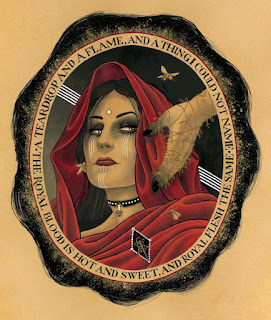

Review: Selected Stories, by Mark Valentine

The stories gathered here have all been published before, but many appeared in hard-to-obtain volumes. The unifying theme is the collapse of empires in the wake of the Great War. Europe, once 'the mighty continent', has been torn apart by years of brutal conflict. The vast majority of people found their lives disrupted, sometimes fatally, but often in bizarrely unpredictable ways. This much is fact. What Mark Valentine adds is his remarkable erudition as he offers us glimpses of the lives of aristocrats, villagers, aesthetes, and wandering visionaries (or charlatans), during a time when that fabulous phenomenon called balance of power is swinging wildly this way or that.

Indeed, the first story is entitled 'A Certain Power', and takes us among the various social classes and factions of Petrograd during the doomed attempt by the Western Allies to assist the White Russian cause. But the power in question is not an earthly one, and its emissaries have a most unusual mission. I found the story very satisfying - a sound example of a fantastical premise taken to a logical conclusion.

'The Dawn at Tzern', by contrast, is a tale of lesser beings - a provincial postal official who stages a small, almost secret, rebellion by not using newly-issued stamps. He prefers those featuring the old emperor Franz Joseph. The minor functionary's moral qualms are contrasted with the rough idealism of a leftist radical and the mystical, probably heretical, antics of the village priest. All await the dawn, and when a spectacular sunrise comes each sees in it the possible fulfilment of their hopes.

'The Walled Garden on the Bosphorus' is a slight tale of a learned man who 'collects' unusual faiths - heresies, cults, near-forgotten creeds. Felix Vrai (the name is surely significant) eventually vanishes, perhaps to search for his unorthodoxy of choice. Or perhaps he vanishes because he has found it. Also very short, but powerful in a Machenesque way, is 'The Amber Cigarette', in which a strange jewel - a 'sphere of worked jasper' - exerts an abnormal fascination. The jewel happens to adorn a cigarette case, and the story is as much a paean to the pleasures of tobacco (a topic that the young Machen explored) as it is a mystical vignette.

The next story, 'Carden in Capaea', is the tale of a tribe not so much lost as overlooked. The Capaean language intrigues a British adventurer, as he struggles to grasp a world (perhaps our 'real' world) that only needs to be truly named to be revealed. It's a somewhat Borgesian tale, or at least it reminded me of the latter's 'Undr', with its quest for a word that is all poetry in itself.

'The Bookshop in Novy Svet' rings the changes on the idea that language can alter reality - if we take the mathematics of the actuary to be a language as potent as the works of any poet. This deliberately Kafkaesque story even features (albeit peripherally) a Doctor K, who assists the Workman's Compensation Society. When he is made redundant the assistant actuary discovers poetry, and comes up with a clever scheme to make money by calculating when a given poet's works will rise sharply in value. But things do not work out quite as planned.

A personal favourite of mine is 'The Ka of Astarakhan'. Here is a first-person narrative given by a dying poet who is also, arguably, a mystic, a buffoon, a charlatan. Playful, intense, and ultimately moving, it is more of a testament to the value of a life lived boldly (if, at times, absurdly) amid the chaos of decaying cultures. It's also a quiet affirmation of the value of the short story, as - like a good poem - it demands to be read and grasped at one sitting.

'The Unrest at Aachen' is, I think, a story that lies somewhere between Machen and Chesterton (especially the latter's The Napoleon of Notting Hill). It's a story of how a minor operative of the Luxembourg secret service prevented a world war from breaking out in 1906. If that sounds slightly ludicrous, well it is in a way. But it's also a fable about the way myth and belief can shape history, for better or worse.

The final story, 'The Mascarons of the Late Empire', is so rich in ideas and imagery that it ought to form the seed-pearl of a fascinating novel. Set in the easternmost city of the recently-defunct Austro-Hungarian Empire, it explores the hazy territories between the personal and the political, as a proto-fascist movement arises, windows are smashed, Jewish graves desecrated, and a single language is imposed on a diverse citizenry. The characters all, in their different ways, represent old Europe, with its romance, stability and belief in progress. All are out of place in a more sordid and brutal world. Yet, the author suggests, there is still hope.

This book is arguably the best 'sampler' of Mark Valentine's highly-regarded fiction. While not every story can be deemed supernatural, they are all imbued with a strangeness and beauty that takes them - and the reader - several removes from what is called realism.

Indeed, the first story is entitled 'A Certain Power', and takes us among the various social classes and factions of Petrograd during the doomed attempt by the Western Allies to assist the White Russian cause. But the power in question is not an earthly one, and its emissaries have a most unusual mission. I found the story very satisfying - a sound example of a fantastical premise taken to a logical conclusion.

'The Dawn at Tzern', by contrast, is a tale of lesser beings - a provincial postal official who stages a small, almost secret, rebellion by not using newly-issued stamps. He prefers those featuring the old emperor Franz Joseph. The minor functionary's moral qualms are contrasted with the rough idealism of a leftist radical and the mystical, probably heretical, antics of the village priest. All await the dawn, and when a spectacular sunrise comes each sees in it the possible fulfilment of their hopes.

'The Walled Garden on the Bosphorus' is a slight tale of a learned man who 'collects' unusual faiths - heresies, cults, near-forgotten creeds. Felix Vrai (the name is surely significant) eventually vanishes, perhaps to search for his unorthodoxy of choice. Or perhaps he vanishes because he has found it. Also very short, but powerful in a Machenesque way, is 'The Amber Cigarette', in which a strange jewel - a 'sphere of worked jasper' - exerts an abnormal fascination. The jewel happens to adorn a cigarette case, and the story is as much a paean to the pleasures of tobacco (a topic that the young Machen explored) as it is a mystical vignette.

The next story, 'Carden in Capaea', is the tale of a tribe not so much lost as overlooked. The Capaean language intrigues a British adventurer, as he struggles to grasp a world (perhaps our 'real' world) that only needs to be truly named to be revealed. It's a somewhat Borgesian tale, or at least it reminded me of the latter's 'Undr', with its quest for a word that is all poetry in itself.

'The Bookshop in Novy Svet' rings the changes on the idea that language can alter reality - if we take the mathematics of the actuary to be a language as potent as the works of any poet. This deliberately Kafkaesque story even features (albeit peripherally) a Doctor K, who assists the Workman's Compensation Society. When he is made redundant the assistant actuary discovers poetry, and comes up with a clever scheme to make money by calculating when a given poet's works will rise sharply in value. But things do not work out quite as planned.

A personal favourite of mine is 'The Ka of Astarakhan'. Here is a first-person narrative given by a dying poet who is also, arguably, a mystic, a buffoon, a charlatan. Playful, intense, and ultimately moving, it is more of a testament to the value of a life lived boldly (if, at times, absurdly) amid the chaos of decaying cultures. It's also a quiet affirmation of the value of the short story, as - like a good poem - it demands to be read and grasped at one sitting.

'The Unrest at Aachen' is, I think, a story that lies somewhere between Machen and Chesterton (especially the latter's The Napoleon of Notting Hill). It's a story of how a minor operative of the Luxembourg secret service prevented a world war from breaking out in 1906. If that sounds slightly ludicrous, well it is in a way. But it's also a fable about the way myth and belief can shape history, for better or worse.

The final story, 'The Mascarons of the Late Empire', is so rich in ideas and imagery that it ought to form the seed-pearl of a fascinating novel. Set in the easternmost city of the recently-defunct Austro-Hungarian Empire, it explores the hazy territories between the personal and the political, as a proto-fascist movement arises, windows are smashed, Jewish graves desecrated, and a single language is imposed on a diverse citizenry. The characters all, in their different ways, represent old Europe, with its romance, stability and belief in progress. All are out of place in a more sordid and brutal world. Yet, the author suggests, there is still hope.

This book is arguably the best 'sampler' of Mark Valentine's highly-regarded fiction. While not every story can be deemed supernatural, they are all imbued with a strangeness and beauty that takes them - and the reader - several removes from what is called realism.

Monday 17 December 2012

The Bells (1926)

In my informal list of 'weird films to watch at Christmas', why not try this screen adaptation of the play that made Sir Henry Irving the first theatrical knight? The original play in which Irving became a Victorian sensation was by Erckmann-Chatrian, one of the great writing teams in horror/supernatural fiction. The film was made by a rather small firm and might have vanished without trace. We're lucky it's still around, because it's a fascinating historical time capsule, and quite entertaining in itself.

Set during a bad winter in 1868, the story concerns Mathias, a leading citizen of a small town in the mountains of southern Alsace. Mathias harbours ambitions to become burgomaster, and is thus keen to extend credit to the customers of his tavern and his flour mill. This upsets his wife, but does indeed guarantee him the support of the townsfolk. Unfortunately for Mathias, he is no position to be generous - he is deep in debt to an unpleasant local bigwig who will soon foreclose and take his property.

What to do? Well, it just so happens that at Christmas, during a terrible blizzard, a rich Jewish merchant travelling to Paris from Warsaw happens by the inn. Baruch (interestingly, given the period of the play and indeed that of the film) is presented as an amiable soul, but he is also incautious. He reveals to Mathias that he carries large sums in gold about his person. Cue an old-school melodramatic murder. The bells of the title are the sleighbells that jingle as poor Baruch breathes his last.

Well, Matthias is in the money. Unfortunately, he is also in a fictional town where a. a young Boris Karloff is playing a mesmerist who can look into 'the secrets of your soul' and b. he is a classic Victorian character, in that he is plagued by his conscience. Cue scenes involving the bells a-jingling, the ghost of Baruch returning (in one very good effects scene the merchant and his murderer play cards), and Mathias quite clearly cracking up. This performance, by the one-legendary Lionel Barrymore, is very theatrical, of course. But he does convey the torment of a man who believes himself to be good and seeks forgiveness, as opposed to the psychopathic type more commonly found in modern thrillers.

Anyway, if you're looking for unusual seasonal viewing, this one is on LoveFilm in an excellent restored version with a good soundtrack. The version on YouTube is less good but still watchable. And here's the first part.

Set during a bad winter in 1868, the story concerns Mathias, a leading citizen of a small town in the mountains of southern Alsace. Mathias harbours ambitions to become burgomaster, and is thus keen to extend credit to the customers of his tavern and his flour mill. This upsets his wife, but does indeed guarantee him the support of the townsfolk. Unfortunately for Mathias, he is no position to be generous - he is deep in debt to an unpleasant local bigwig who will soon foreclose and take his property.

What to do? Well, it just so happens that at Christmas, during a terrible blizzard, a rich Jewish merchant travelling to Paris from Warsaw happens by the inn. Baruch (interestingly, given the period of the play and indeed that of the film) is presented as an amiable soul, but he is also incautious. He reveals to Mathias that he carries large sums in gold about his person. Cue an old-school melodramatic murder. The bells of the title are the sleighbells that jingle as poor Baruch breathes his last.

Well, Matthias is in the money. Unfortunately, he is also in a fictional town where a. a young Boris Karloff is playing a mesmerist who can look into 'the secrets of your soul' and b. he is a classic Victorian character, in that he is plagued by his conscience. Cue scenes involving the bells a-jingling, the ghost of Baruch returning (in one very good effects scene the merchant and his murderer play cards), and Mathias quite clearly cracking up. This performance, by the one-legendary Lionel Barrymore, is very theatrical, of course. But he does convey the torment of a man who believes himself to be good and seeks forgiveness, as opposed to the psychopathic type more commonly found in modern thrillers.

Anyway, if you're looking for unusual seasonal viewing, this one is on LoveFilm in an excellent restored version with a good soundtrack. The version on YouTube is less good but still watchable. And here's the first part.

Saturday 15 December 2012

The Yellow Leaves

A bit of blatant advertising, now, for the noble cause of publishing poetry on that stuff called paper that's still apparently being made somewhere. The Yellow Leaves series offers 'tantalising glimpses of a reality beyond our comprehension', and I'm sure we're all down with that. The third leaflet in the series features work by the excellent Cardinal Cox. And this is what one side of the 'paper' looks like...

Click to make it bigger so you can read the various bits. Note the reference to Ambrose Bierce's fictional medium, Bayrolles, who was always sticking his oar in to tie up a few loose plot strands. Also note links etc allowing you to contact D.J. Tyrer, editor of the series, and of course the cardinal himself.

He's making a list...

The Japanese horror movie boom launched a number of TV series that sought - quite reasonably - to cash in. One interesting series, which can be found in fragmentary form on YouTube, is entitled Kazuo Umezu's Horror Theater. Umezu is a very popular manga writer, and I think the TV adaptations of his work are pretty good. The Diet, in particular, manages to pack a lot of disturbing stuff into a mere sixty-odd minutes. The reason I'm mentioning this in mid-December is simply that one of Mr Omezu's tales is a Christmas number entitled The Present. Here's how it starts - an object lesson in the need to be very careful what you tell children at this time year. I'm also impressed (though of course to the intended audience it would be unremarkable) by the juxtaposition of Shinto images with trad Christmassy stuff.

Saturday 8 December 2012

The Silent House (2010)

I've watched precisely one Uruguayan horror film so far, and I quite enjoyed it. The premise is simple - shy teenager Laura and her amiable old dad, the rather oddly-named Wilson, move into a remote, rather ramshackle house to do some gardening and generally tidy the place up. We first see them approaching the property through fields, climbing through fences and so on, establishing that, yes, it's kilometres from anywhere. At the house they meet the owner, an old friend of dad's, who helps them get settled in and promises to pop back with some food later.

So far, so familiar. We are expecting Something Sinister to happen. Sure enough, when Laura and her father settle down for the night, the girl hears someone outside. Her father is already asleep, of course, and when she wakes him up he tells her not to worry - there's nobody about. Then, when he nods off again, she hears someone moving about upstairs. They have been warned not to visit the upstairs rooms because of structural problems. But when she wakes dad again, and he sees she's in a bit of a state, he reluctantly agrees to investigate, if she promises to go to sleep when he gets back.

Needless to say, he doesn't get back. Instead Laura hears an ominous cry, followed by a dragging sound. Oo-er. We are well within conventional 'stalk-and-slash' territory, and we are less than half an hour into the movie (which runs for over ninety minutes). Not surprisingly, by this point I was starting to feel some irritation, muttering about derivative ideas and horror movie conventions. But I kept watching, partly because it is a visually arresting film. Despite the familiar setting (oh, look, a grotty kitchen, and here's a bedroom full of antique furniture) the director, Gustavo Hernandez, does a fine job of making the house genuinely eerie.

And, as the action develops, things do begin to take an odd turn - disturbing, rather than horrific. There is a 'secret room' upstairs, and during a couple of scenes we see what appears to be a child. Laura escapes from the knife-wielding killer (who we have glimpsed very briefly) and runs into the bush, only to encounter the house's owner. He insists on going on to the house and looking for his old friend Wilson, whereupon the killer gets him in the time-honoured fashion, leaving him bloodied and bound on the kitchen floor. He does not escape. But Laura does, in a way. The ending is strange, memorable, and has a touch of the fairytale. Whether this country as a supernatural horror film, I don't know. But it's certainly worth a look. And (predictably) there's already an American remake.

Firstly, this film is reportedly based on a real events that happened in Uruguay in 1944. Secondly - and this I find truly impressive - the entire film is shot in one long take. That take is 79 minutes long. I didn't know this until after I'd watched it, but thinking back there is no moment when an obvious 'jump' occurs. The camera follows Laura all the time. This makes the central performance by Florencia Colucci all the more impressive. At first I found her 'terrified little girl who jumps at everything' a bit irritating, wondering whether she would show a bit more fight and initiative. I needn't have worried. While it's not an especially scary movie, it is a remarkably accomplished one.

So far, so familiar. We are expecting Something Sinister to happen. Sure enough, when Laura and her father settle down for the night, the girl hears someone outside. Her father is already asleep, of course, and when she wakes him up he tells her not to worry - there's nobody about. Then, when he nods off again, she hears someone moving about upstairs. They have been warned not to visit the upstairs rooms because of structural problems. But when she wakes dad again, and he sees she's in a bit of a state, he reluctantly agrees to investigate, if she promises to go to sleep when he gets back.

Needless to say, he doesn't get back. Instead Laura hears an ominous cry, followed by a dragging sound. Oo-er. We are well within conventional 'stalk-and-slash' territory, and we are less than half an hour into the movie (which runs for over ninety minutes). Not surprisingly, by this point I was starting to feel some irritation, muttering about derivative ideas and horror movie conventions. But I kept watching, partly because it is a visually arresting film. Despite the familiar setting (oh, look, a grotty kitchen, and here's a bedroom full of antique furniture) the director, Gustavo Hernandez, does a fine job of making the house genuinely eerie.

And, as the action develops, things do begin to take an odd turn - disturbing, rather than horrific. There is a 'secret room' upstairs, and during a couple of scenes we see what appears to be a child. Laura escapes from the knife-wielding killer (who we have glimpsed very briefly) and runs into the bush, only to encounter the house's owner. He insists on going on to the house and looking for his old friend Wilson, whereupon the killer gets him in the time-honoured fashion, leaving him bloodied and bound on the kitchen floor. He does not escape. But Laura does, in a way. The ending is strange, memorable, and has a touch of the fairytale. Whether this country as a supernatural horror film, I don't know. But it's certainly worth a look. And (predictably) there's already an American remake.

Firstly, this film is reportedly based on a real events that happened in Uruguay in 1944. Secondly - and this I find truly impressive - the entire film is shot in one long take. That take is 79 minutes long. I didn't know this until after I'd watched it, but thinking back there is no moment when an obvious 'jump' occurs. The camera follows Laura all the time. This makes the central performance by Florencia Colucci all the more impressive. At first I found her 'terrified little girl who jumps at everything' a bit irritating, wondering whether she would show a bit more fight and initiative. I needn't have worried. While it's not an especially scary movie, it is a remarkably accomplished one.

Thursday 6 December 2012

Of a book and its cover

The unexpected arrival of a beautiful book is always pleasant. In this case I know the book's contents will live up to its cover. Or rather, covers. Selected Stories by Mark Valentine, newly published by Swan River Press, has a rather splendid blue and gold dust-jacket, but beneath it we find this:

A slightly inept scan, but you get the picture, so to speak.

A much cleverer person would see this beautiful, antique oil lamp as an apt metaphor - one that illuminates the stories gathered in this volume. According to the flyleaf, these stories 'are about individuals caught up in the endings of old empires - and of what comes next'.

This is familiar territory for Valentine, one of the most intellectually accomplished authors of what is loosely termed weird fiction. I've long admired his work. Many authors have tackled the decline into chaos of Europe, once dubbed the mighty continent by someone or other (probably a Frenchman), now apparently far gone in stagnation and riven by internal dissent. In literary terms decay, uncertainty and failure are more interesting than rip-roaring success, unless of course the latter ends in some terrible disillusion. The power fantasies of politicians and the crazier revelations of prophets are more goal-orientated, of course. And then there are the artists, poets, visionaries, charlatans... I look forward to meeting them all in in these stories.

The titles - rather wondrous in themselves - are as follows:

A Certain PowerA mascaron is 'a decorative element in the form of a sculpted face or head of a human being or an animal'. Wonderful thing, the internet. Not all change is for the worse.

The Dawn at Tzern

A Walled Garden on the Bosphoros

Carden in Capaea

The Bookshop in Novy Svet

The Autumn Keeper

The Amber Cigarette

The Ka of Astarakahn

The Original Light

The Unrest at Aachen

The Mascarons of the Late Empire

Tuesday 4 December 2012

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

'The Fifth Moon'

This is the final part of a running review of Lost Estates by Mark Valentine (Swan River Press 2024) The final story in this splendidly pr...

-

Some good news - Helen Grant's story 'The Sea Change' from ST11 has been nominated for a Bram Stoker Award. This follows an inqu...

-

Go here to purchase this disturbing image of Santa plus some fiction as well. New stories by: Helen Grant Christopher Harman Michael Chis...

-

Paul Lowe cover art, excellent as usual Though warm my welcome everywhere, I shift so frequently, so fast, I cannot now say where I was T...