The final story in the collection The Uncertainty of All Earthly Things is, rather cunningly, not so much a story as a collection of notes that might make any number of cracking tales. It consists of a series of entries in a journal starting on 13th September 2001 and ending in the following September. Not surprisingly the author finds himself in small towns, visiting bookshops, the odd record shop, and of course historic buildings.

Along the way we learn about Mark Valentine's literary tastes. I've heard of most of the authors he mentions, read somewhat fewer of them. He is of course a Machen fan, but also an admirer of the late W.G. Sebald, somewhat less keen on Simon Raven. A 'PJB' is, I presume, the author Peter Bell, who joins Mark for some bibliophile adventures. Along the way we find the killing of the last wolf in England (allegedly), some nice pubs, and find out what a cittern is. This story-cum-essay is a tad Borgesian in its eclecticism and a very pleasant, relaxing end to the collection.

So, overall, this is a darn good book. Anyone who likes well-crafted, erudite, and unsettling fiction will not be disappointed. And well done Zagava for producing such a fine hardback, while also offering TUOAET as a nicely-priced paperback.

I received a review copy of this book from the publisher.

Saturday, 31 March 2018

Friday, 30 March 2018

'As Blank As the Days Yet to Be'

The penultimate story Mark Valentines The Uncertainty of All Earthly Things is a tale of the cockatrice. No, missus, really. From it I learned that a cockatrice is a hybrid cock-snake (I'm not making this up) and has gorgonesque powers to turn other living things to stone. I wasn't aware of cockatrice legends from around England, one of which involved someone lowering a mirror into its lair so it zapped itself. We are an ingenious people...

The penultimate story Mark Valentines The Uncertainty of All Earthly Things is a tale of the cockatrice. No, missus, really. From it I learned that a cockatrice is a hybrid cock-snake (I'm not making this up) and has gorgonesque powers to turn other living things to stone. I wasn't aware of cockatrice legends from around England, one of which involved someone lowering a mirror into its lair so it zapped itself. We are an ingenious people...In the story the narrator sets out in search of more folklore and finds it in a small village, along with something else - the remains of an ancient turf maze. These are fascinating, not least because nobody could get lost in them.

Well, not in a conventional sense I gleaned the possibility that the young man the author meets, Anthony, is not just a helpful local but something more, and that the two walking the maze has great significance. Unfortunately I found the story baffling so I can't be sure how successful it might seem to someone who understood it.

Sunday, 25 March 2018

'Martin's Close'

Here's Alan Brown's evocative illustration for M.R. James classic tale of ghostly vengeance, which prompted me to think about the story again - as good artwork does. It's a disturbing read, but I suspect some modern folk might struggle a bit with the period dialogue in the court transcript. For me it's one of the best examples of a historical ghost story - one set in a bygone era that is expertly brought to life by the author. In Judge Jeffries James offers a very believable portrait of a real villain, acting as a kind of counterweight to George Martin, who's pretty much a broken man by the time his trial begins.

You can hear a discussion of this slightly neglected story at the excellent A Podcast to the Curious, and there a lot of useful links on the site, too.

http://www.mrjamespodcast.com/2012/06/episode-14-martins-close/

Look Ma, Top o' the World!

Okay so it wasn't No. 1 for long, but still. If Mr Spielberg is interested I'm in most evenings.

Wednesday, 21 March 2018

'The Uncertainty of All Earthly Things'

The title story in Mark Valentine's new collection from Zagava is a gentle tale of strange events on the borders of what we term normal life.

A man goes to a small rural community to curate a museum dedicated to a not-very-famous explorer. In his new home he becomes fascinated by the artefacts he now has in his care, particularly ones which bear odd carvings in what might be an unknown language. Then the narrator encounters a pleasant, eccentric woman engaged in taking rubbings in the church. It turns out that she is also trying to create a new Tarot specific to the odd Cornish village of Sancreed.

The setting of Sancreed is beautifully evoked, and the story relies on the Machenesque notion that some places are closer (in some dimension) to a higher truth than most. The revelation that the characters experience at the old 'rocket shed' on the westernmost tip of the peninsula is awesome in the old-fashioned sense, an epiphany that it may take them a lifetime to truly know. This is, in a way, a love story, emphasising that the greatest mysteries of life and time are always close at hand.

More from this running review soon. I've reached that point in the book where I slow down a bit because I don''t want to get to the end. But I'm definitely getting there, regardless...

A man goes to a small rural community to curate a museum dedicated to a not-very-famous explorer. In his new home he becomes fascinated by the artefacts he now has in his care, particularly ones which bear odd carvings in what might be an unknown language. Then the narrator encounters a pleasant, eccentric woman engaged in taking rubbings in the church. It turns out that she is also trying to create a new Tarot specific to the odd Cornish village of Sancreed.

The setting of Sancreed is beautifully evoked, and the story relies on the Machenesque notion that some places are closer (in some dimension) to a higher truth than most. The revelation that the characters experience at the old 'rocket shed' on the westernmost tip of the peninsula is awesome in the old-fashioned sense, an epiphany that it may take them a lifetime to truly know. This is, in a way, a love story, emphasising that the greatest mysteries of life and time are always close at hand.

More from this running review soon. I've reached that point in the book where I slow down a bit because I don''t want to get to the end. But I'm definitely getting there, regardless...

Quatermass and the Tits

I've just watched Lifeforce (1985) all the way through for the first time in many years. I have a few thoughts. Oh dearie me, yes.

For a start, this is a film with many real virtues. Unfortunately none of them have much to do with the script or the lead performances. Nope, it's all down to the effects, the general production values, Tobe Hooper's solid direction, and a very good (if somewhat under-used) supporting cast. Much of the blame for this hefty box-office flop lies with Colin Wilson's original story, which - as my clickbaity title for this post hints - is wildly derivative stuff with a sweaty whiff of soft porn. Wilson's novel The Space Vampires I have not read. But if the script is any guide, it must be a doozy. But let's consider those virtues I mentioned first.

For a start, John Dyskra's space effects are rather good, especially in the opening sequence when the spacecraft Churchill approaches Halley's Comet and identifies a 150 mile-long alien spaceship lurking in the plasma fog around the nucleus. I mean, that's a good opener. They even try to add a bit of Real Science by having the Churchill (it's an Anglo-American space mission you see) powered by the Nerva rocket. Nerva was a real nuclear rocket engine researched in the early Sixties, thought it could not provide the continuous 1g thrust claimed here. Still, good try.

Tuesday, 20 March 2018

Saturday, 17 March 2018

New books by me

"Two new books, Dave? What a splendid chap you are, well done!"

"Gosh, yes, you're so prolific."

"Please have all our money."

Factually speaking, these books are about: changelings, 'the Good Folk', a haunted mansion, unwise ghost-hunting TV production methods, monsters, a town near the Welsh border called Machen, and other things.

"Gosh, yes, you're so prolific."

"Please have all our money."

Factually speaking, these books are about: changelings, 'the Good Folk', a haunted mansion, unwise ghost-hunting TV production methods, monsters, a town near the Welsh border called Machen, and other things.

'The Scarlet Door' and 'Vain Shadows Flee'

The next two stories in The Uncertainty of All Earthly Things were both published by me in ST, and are therefore brilliant. Well, okay, they're very good. 'The Scarlet Door' sees Mark Valentine in familiar territory - the world of niche collectors. In this case the narrator haunts small, cluttered bookshops in search of rare volumes. Not valuable books per se, you understand, but ones so obscure that they have never been catalogued or shelved in a library. In the eponymous scarlet volume he finds more than he bargained for. Or does he? All we can be sure of is that books are portals to strange worlds, and almost unknown books can offer routes to the strangest realms of all.

'Vain Shadows Flee' is a tribute to the late Joel Lane. Not a horror tale as such, it is a meditation on loss. In this case the loss is of Bide-y, a tramp who lived by a canal and sang 'Abide With Me', then vanished. From this apparently thin seam the author weaves a compelling picture of the margins of our increasingly shabby, callous society.

There is beauty even in decline, of course. Thus on a morning in early February: 'The stalks of grass were like white daggers, and each paving stone was an atlas of frosted glass.' One of the pleasures of this book is the high standard of the writing, which is often wryly humorous but sometimes, as in this story, sombre and elegiac in tone.

More from this running review very soon.

'Vain Shadows Flee' is a tribute to the late Joel Lane. Not a horror tale as such, it is a meditation on loss. In this case the loss is of Bide-y, a tramp who lived by a canal and sang 'Abide With Me', then vanished. From this apparently thin seam the author weaves a compelling picture of the margins of our increasingly shabby, callous society.

There is beauty even in decline, of course. Thus on a morning in early February: 'The stalks of grass were like white daggers, and each paving stone was an atlas of frosted glass.' One of the pleasures of this book is the high standard of the writing, which is often wryly humorous but sometimes, as in this story, sombre and elegiac in tone.

More from this running review very soon.

Thursday, 15 March 2018

'Yes, I Knew the Venusian Commodore'

Best title I've read in a good while, and a good story too. Mark Valentine's collection The Uncertainty of All Earthly Things has a few recurring themes. One is the torment that sensitive, thoughtful individuals must suffer in a world that is crass and indifferent. Another is loneliness, the yearning for a connection, a sense of order and belonging.

'Yes, I Knew the Venusian Commodore' tackles these themes by the roundabout route of imagined low-budget sci-fi. In the obscure film Venus Invades Us the eponymous commander was played by an actor rejoicing in the screen name of Triton. Triton put in one of those compelling performances that can raise a film to cult status. Fans materialise, while work remains sparse.

And then, as sometimes happens, Triton began to identify with his one significant role so much that he believed himself to be in touch with aliens. The only problem is that the Venusians are in fact peaceful. It's those warlike Martians you've got to watch. And so the commodore, promoting himself to admiral, envisaged a follow-up in which he leads an interplanetary armada to bring peace to the solar system. But death claims him before his project can be realised.

This could be presented as broad tragi-comedy, but instead the narrator makes it clear that Triton, deluded or not, is admirable in his devotion to peace. The envisaged sequel All Against Mars is an allegory about the struggle on Earth between love and hate, creation and destruction. Triton is in some ways the archetypal English eccentric, but his mission is not absurd.

More from this running review soon.

Tuesday, 13 March 2018

Ghost - Review

Antispoiler alert - Ghost by Helen Grant is not a supernatural tale. It is, however, a modern Gothic novel that anyone who likes Helen's other work will enjoy. So, having said that, what's it about?

The setting is a big, isolated house in the Scottish countryside. There live Ghost, real name Augusta, and her grandmother. Ghost knows that, beyond the dense forest that fringes the estate, World War 2 is raging. Bombs fall onto terrified civilians, war machines clash by land, sea, and air, and while the men are away fighting women are drafted into factories to make munitions.

Grandmother is protecting Ghost from a world in chaos. Grandmother sometimes goes into town for supplies, but ghost - who is seventeen - never ventures as far as the road. It is not safe.

But the great house is crumbling, and a winter storm brings down a section of roof. Grandmother calls in a builder to repair the damage, and the builder brings his teenage son, Tom. Ghost, as usual, has to hide in the attic. Nobody knows of her existence. If she is glimpsed peering out of a window she might well be a ghost. But when she sees Tom she is fascinated and, helped by chance, she establishes an indirect connection.

Then Ghost's world changes. Grandmother goes to the town, but does not return. As in many Gothic novels the secluded life of the sensitive young woman, who has never had a playmate and knows the world only from books, must end. Ghost, with Tom's help, begins to make sense of her small world, and learns more of the world beyond it. There are a series of revelations and twists, right to the end, with just about every Gothic trope deployed to good effect. And I have to admit that the ending surprised me, yet made perfect sense in the context of the novel.

Ghost has, rightly I think, been compared to the stand-alone novels of Ruth Rendell. While Helen Grant is not so coldly clinical in her treatment of her characters, she does not flinch from making hard but logical decisions about their fates. This is a compelling read, one for fans of Helen Grant's work, and a good place for new readers to start.

Monday, 12 March 2018

The Haunting Hour (2011-14)

I never read R.L. Stine's Goosebumps series of spooky tales aimed at youngsters. Sadly, I was far too old for them - or so I thought. But having seen Stine on screen, I think I might have been a bit sniffy just because they were aimed at kids.

The Haunting Hour, a TV series bearing Stine's name, is available free to watch on YouTube (as well as on Amazon Prime, without ads). It's an anthology series, with 20 minute episodes offering either stand-alone or two-part stories. These were run in three - hence the title. There were four seasons in all, and while some episodes are a little flat and obvious, some are pretty good. I've seen far worse attempts at anthology series for adults in recent years.

THH is almost a Twilight Zone for kiddies, as some episodes offer science fiction rather than supernatural horror. Most, though, go for the familiar Hallowe'en tropes of the haunted house, the ghost, the vampire etc. And there's nothing wrong with that.

You can find the YouTube Haunting Hour channel here. If you're feeling a bit under the weather and in the mood for relatively mild chills, this might be your cup of tea. Or, of course, if you want to find some family-friendly viewing to imbue a younger person this might just work. Some episodes come with a warning that they are not suitable for smaller children, btw.

Here is an entire episode. It's a tad more bleak than some, but gives a good idea of what's on offer.

|

| Oh God no! Not the clowns! |

The Haunting Hour, a TV series bearing Stine's name, is available free to watch on YouTube (as well as on Amazon Prime, without ads). It's an anthology series, with 20 minute episodes offering either stand-alone or two-part stories. These were run in three - hence the title. There were four seasons in all, and while some episodes are a little flat and obvious, some are pretty good. I've seen far worse attempts at anthology series for adults in recent years.

THH is almost a Twilight Zone for kiddies, as some episodes offer science fiction rather than supernatural horror. Most, though, go for the familiar Hallowe'en tropes of the haunted house, the ghost, the vampire etc. And there's nothing wrong with that.

|

| Albert Steptoe - The Return! |

You can find the YouTube Haunting Hour channel here. If you're feeling a bit under the weather and in the mood for relatively mild chills, this might be your cup of tea. Or, of course, if you want to find some family-friendly viewing to imbue a younger person this might just work. Some episodes come with a warning that they are not suitable for smaller children, btw.

Here is an entire episode. It's a tad more bleak than some, but gives a good idea of what's on offer.

Saturday, 10 March 2018

'The Mask of the Dead Mamilius' & 'In Cypress Shades'

Two linked stories, now, from Mark Valentine's The Uncertainty of All Earthy Things. Both feature an eccentric, intense theatre director, Robert Hobbes.

'In Cypress Shades' is told from the perspective of a producer seeking to put on a production of Milton's 'Comus', a strange masque the poet wrote in his youth. Hobbes, a finely-drawn example of the director-as-tyrant, finds a make-up artist whose work is so good that it eliminates the need for masks in the masque. Unfortunately, as the narrator discovers, the mysterious artist's work has an enduring quality.

'The Mask of the Dead Mamilius' concerns the tragic small son of Leontes in The Winter's Tale, who dies because his father - another tyrant - falsely believes he had been cuckolded. In this short tale a young actress takes the part of Mamilius, who is required by Hobbes to haunt Leontes through to the bitter-sweet end of the drama. Unfortunately the haunting proves more than merely theatrical...

Theatrical ghost stories are often gentle, whimsical efforts, but these have a more disturbing tone. Changing faces, they warn us, is always a problematic activity, and artistry is akin to magic,

More from this running review very soon.

'In Cypress Shades' is told from the perspective of a producer seeking to put on a production of Milton's 'Comus', a strange masque the poet wrote in his youth. Hobbes, a finely-drawn example of the director-as-tyrant, finds a make-up artist whose work is so good that it eliminates the need for masks in the masque. Unfortunately, as the narrator discovers, the mysterious artist's work has an enduring quality.

'The Mask of the Dead Mamilius' concerns the tragic small son of Leontes in The Winter's Tale, who dies because his father - another tyrant - falsely believes he had been cuckolded. In this short tale a young actress takes the part of Mamilius, who is required by Hobbes to haunt Leontes through to the bitter-sweet end of the drama. Unfortunately the haunting proves more than merely theatrical...

Theatrical ghost stories are often gentle, whimsical efforts, but these have a more disturbing tone. Changing faces, they warn us, is always a problematic activity, and artistry is akin to magic,

More from this running review very soon.

Friday, 9 March 2018

'Zabulo'

'Let me commend to you the work of the Churches Conservation Trust...'

So begins Mark Valentine's tale of a gentleman who - like so many protagonists in M.R. James' stories - likes looking into churches on his travels. He finds one that seems to be in the wrong place, and in it he discovers some rather odd cards.

I never gave much thought to those hymn numbers that are seen in churches, usually stuck in a frame on a pillar near the pulpit. But, as this story makes clear, they must be printed by someone and are bound to be stored in or near the church.

But why, in this case, are there so many numbered cards? And why were so many of them printed by one 'Zabulo'. When the narrator repeats the unusual name, things happen...

This is an atmospheric vignette, one that skirts the dark waters of medieval magic, numerology, and related matters. I enjoyed it when it first appeared in the Ghosts & Scholars newsletter, and I enjoyed it the second time.

More from this running review very soon. Let me remind you that, while The Uncertainty of All Earthly Things is available as a limited edition hardback, there will also be an unlimited paperback edition for the fiscally challenged. And those who don't get review freebies, obviously.

'Goat Songs'

Mark Valentine is probably a record collector. I offer this opinion because he pretty much nails the atmosphere of second-hand record shops in 'Goat Songs'. His narrator stumbles across - or is lured by? - an obscure album by one of those Sixties groups who were into mysticism, folklore, and mind-bending antics.

Like the previous story, 'Goat Songs' is about the enchantments that music can weave. The title refers to the album title, the group being Satyr. The climax of the story is, of course, the playing of the record. But before this we have learned that the 'hero' is a lost soul, living in a van with his record collection, often going without food so he can buy more. So when the final track on the album does not start the reader half-knows what is coming - the absolute release from the bleakly mundane that music so often promises, but so rarely delivers.

I'm making good progress with this collection and will provide more review fragments soon.

Thursday, 8 March 2018

International (Spooky) Women's Day 2

I've just received the latest copy of the Ghosts & Scholars M.R. James Newsletter. It seems only fair to point out that it's editor, Ro Pardoe, is one of the great women of weird fiction. She does not blow her own trumpet and deserves to be better known. She is a retiring Titan (or possibly a quiet Colossus) of genre fiction, one of those people who have been busy in fandom and small press publishing for decades and brought pleasure to thousands (at least) for no material reward.

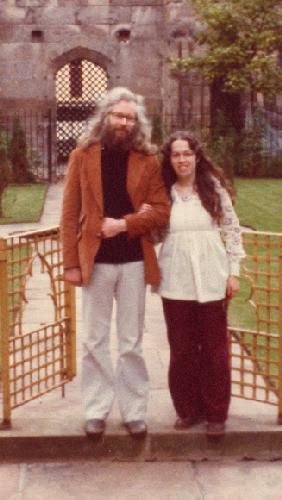

I think it was through a dealer's catalogue that I found out about Ro's magazine (then simply Ghosts & Scholars) and subscribed to it. I also bought some of her excellent Haunted Library chapbooks. I have since met Ro and her husband Darroll on a few (far too few) occasions, and found them as pleasant and erudite in real life as they are on the page. Ro doesn't 'do' the internet, wbich might explain why she is not as well-known as other editors. But her work on M.R. James and related authors is a monument to tenacity and, yes, scholarship.

You can find out a lot more about Ro's work at the G&S website, though it has been dormant for some time.

Here are Ro and Darroll at Seacon in 1979, long before I knew them. We all had so much more hair, then. I'm sure they won't mind me posting this pic. It's all in good fun, guys.

Guys...?

International (Spooky) Women's Day

The ghost story was often seen as an essentially 'feminine' sub-genre in Victorian times. Genteel ladies seem to have woven ghost stories by the square mile for all those new, flourishing periodicals. But if the form was dismissed by 'serious' critics, that did not stop female writers producing some classics of the genre. Here are a few.

'The Shadows on the Wall' by Mary E. Wilkins Freeman. A clever, psychological tale of a bereavement that casts a literal shadow over a far from happy family. It's a simple idea brilliantly executed by a very accomplished American author.

'The Library Window' by Margaret Oliphant. This prolific Scottish author produced more restrained and religious-toned stories. This tale of a convalescing girl confined to a bedroom is a bit more 'modern' and disturbing, though. She becomes fascinated by what is supposedly a false window in the old university library opposite. A strange man is sometimes visible in the window...

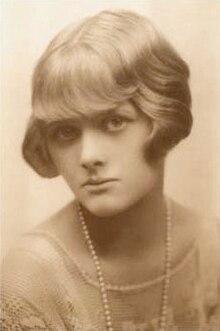

'Don't Look Now' - Daphne Du Maurier. The film adaptation is faithful to the weirdness of the original tale, but even if you know the ending it remains shocking. The theme of a dead child haunting its parents is not uncommon, but the way Du Maurier twists the psychic sub-plot is truly strange. All of her short fiction is worth seeking out. A true original.

'The Tower' - Marghanita Laski. Not an easy one to find, and a very short tale, but extremely effective. It's an original idea that's been copied many times since it first appeared in Lady Cynthia Asquith's Third Ghost Book 1955. It has been reprinted at least once since. No spoilers here!

And finally, here is a (somewhat dodgy VHS) version of 'Three Miles Up' by Elizabeth Jane Howard, a story based on her canal boating adventures with Big Bad Bob Aickman.

Wednesday, 7 March 2018

'Listening to Stonehenge'

The Uncertainty of All Earthly Things by Mark Valentine is, unsurprisingly, proving to be a first-rate collection. 'Listening to Stonehenge' is a tale of an expert on classical music contracted compile a CD of British music. The problem is that the theme is monuments, and there are few - if any - suitable pieces. So begins a quest for obscure works that leads to a forgotten female composer of the inter-war years, and a piece entitled 'Stonehenge'.

This is a tale of the gig economy, interestingly enough, with our narrator making a precarious living writing sleeve notes etc for several employers. It also offers amusing insights into the world of cheap classic music publishing - the 'Glorious Britain' stuff, complete with 'Spitfire over the Cliffs of Dover' cover. It's a slight tale, but the finale, in which the expert flees a bizarre, disturbing rendition of the elusive work, has just the right touch of surreal nightmare. It's a bit Dead of Night, in fact - that's a hint, but I hope not a spoiler.

More from this running review very soon. The next one may have goats...

Perhaps I should include the list of contents while I'm about it, as the titles are so evocative.

This is a tale of the gig economy, interestingly enough, with our narrator making a precarious living writing sleeve notes etc for several employers. It also offers amusing insights into the world of cheap classic music publishing - the 'Glorious Britain' stuff, complete with 'Spitfire over the Cliffs of Dover' cover. It's a slight tale, but the finale, in which the expert flees a bizarre, disturbing rendition of the elusive work, has just the right touch of surreal nightmare. It's a bit Dead of Night, in fact - that's a hint, but I hope not a spoiler.

More from this running review very soon. The next one may have goats...

Perhaps I should include the list of contents while I'm about it, as the titles are so evocative.

To the Eternal One

The Key to Jerusalem

Listening to Stonehenge

Goat Songs

Zabulo

In Cypress Shades

The Mask of the Dead Mammilius

Yes, I Knew the Venusian Commodore

The Scarlet Door

Vain Shadows Flee

The Uncertainty of All Earthly Things

as blank as the days yet to be

Notes on the Border

Monday, 5 March 2018

'The Key to Jerusalem'

The second story in Mark Valentine's collection The Uncertainty of All Earthly Things keeps the reader in the Middle East. He begins by reminding us how inextricably entwined British imperial shenanigans were in the current state of the region.

The second story in Mark Valentine's collection The Uncertainty of All Earthly Things keeps the reader in the Middle East. He begins by reminding us how inextricably entwined British imperial shenanigans were in the current state of the region.A group of British army cooks in Allenby's army, which is fighting the Turks, are sent out to forage for chickens. They instead encounter the Mayor of Jerusalem, who wishes to surrender. The keys of the city are offered, and duly passed on to senior officers - but one extra key, wrapped in a scrap of paper, is given to the cook covertly by the mayor. The cook passes it to an army chaplain. The paper seems to depict a strange coat of arms...

The story is told in the form of three transcripts of interviews with the cook, the chaplain (in old age) and an expert on heraldry. The key is linked a missing order of Crusaders, it is claimed. But the man who went in search of the hidden truth is long since vanished.

There is an elusive magic in this story, reminiscent of Borges' intellectual puzzles that leave the reader feel that he's playing a game without knowing the rules. I liked it, others might not appreciate its ambiguity. But this is a story about the Middle East, and simple resolutions are not available.

More from this running review soon! I'm enjoying this book - it makes an ideal read for snowbound misanthropes.

Sunday, 4 March 2018

The Uncertainty of All Earthy Things - Running Review

A new small press publisher (to me) is Germany's Zagava, which produces limited hardback editions, but also offers unlimited paperbacks. A good policy! The first book they sent me for review is by ST regular, Machen scholar, bibliophile and all-round good egg Mark Valentine. I pinched this image from Zagava's Facebook page (see link above) which also links to its online store here.

So here I go, reviewing a book by someone I know and like. That's pretty much how 90 per cent of 'proper' book reviewing works, of course. But various things happening lately in the rather incestuous world of small press publishing makes me digress here. I will not give something a free pass if I don't think it's good enough. If an author I know and count as a friend writes a stinker I may be unwilling to pan it, but I will not praise it to the skies.

Right, let us move on. The first story in TUOAET is 'To the Eternal One'. It's a period piece, set 'between the wars', in which a group of (somewhat) likeable con-artists travel to Palmyra. The gang have been making a good living forging title documents for people who want to be princes, archbishops etc. The trick - a clever one - is to use the titles of the old Crusader Kingdoms of the Middle East. But things get a little hot for the in England, so they go to the ancient Syrian city to attempt something more ambitious - passports to the afterlife. As the protagonist investigates the city's darker areas to glean 'authentic' artefacts and images, he begins to sense the presence of what might be The Unknown God of the Palmyrans.

This summary is very crude and perhaps misleading. If this is a horror story, it is about the horror we all feel when life is too chaotic and shoddy to be borne, but the alternative seems even worse. It is certainly a weird tale, firmly rooted in the tradition of Machen and Blackwood. There can be no easy resolutions, because deities - or things like them - are not easygoing. It is a fine start to the collection.

More soon from this running, or possibly shambling, review.

So here I go, reviewing a book by someone I know and like. That's pretty much how 90 per cent of 'proper' book reviewing works, of course. But various things happening lately in the rather incestuous world of small press publishing makes me digress here. I will not give something a free pass if I don't think it's good enough. If an author I know and count as a friend writes a stinker I may be unwilling to pan it, but I will not praise it to the skies.

Right, let us move on. The first story in TUOAET is 'To the Eternal One'. It's a period piece, set 'between the wars', in which a group of (somewhat) likeable con-artists travel to Palmyra. The gang have been making a good living forging title documents for people who want to be princes, archbishops etc. The trick - a clever one - is to use the titles of the old Crusader Kingdoms of the Middle East. But things get a little hot for the in England, so they go to the ancient Syrian city to attempt something more ambitious - passports to the afterlife. As the protagonist investigates the city's darker areas to glean 'authentic' artefacts and images, he begins to sense the presence of what might be The Unknown God of the Palmyrans.

This summary is very crude and perhaps misleading. If this is a horror story, it is about the horror we all feel when life is too chaotic and shoddy to be borne, but the alternative seems even worse. It is certainly a weird tale, firmly rooted in the tradition of Machen and Blackwood. There can be no easy resolutions, because deities - or things like them - are not easygoing. It is a fine start to the collection.

More soon from this running, or possibly shambling, review.

Thursday, 1 March 2018

Snowy Ghosty

It's snowing a bit in Britain and everyone is - as our American cousins put it - 'losing their shit' over a bit of bad weather in winter. A good time, then, to ponder some supernatural tales in which snow is pretty much central. Stories in which there'd be a ghostly no show if there was no snow.

1. 'The Glamour of the Snow'

Algernon Blackwood's 1912 tale of a somewhat reclusive, sensitive Englishman on holiday in Switzerland. He feels estranged from his countrymen and women, but finds a sympathetic skating partner on the rink at midnight. The mysterious female companion entrances him, until eventually he is lured out of the town and up into the Alps...

2. 'The Woman of the Saeter'

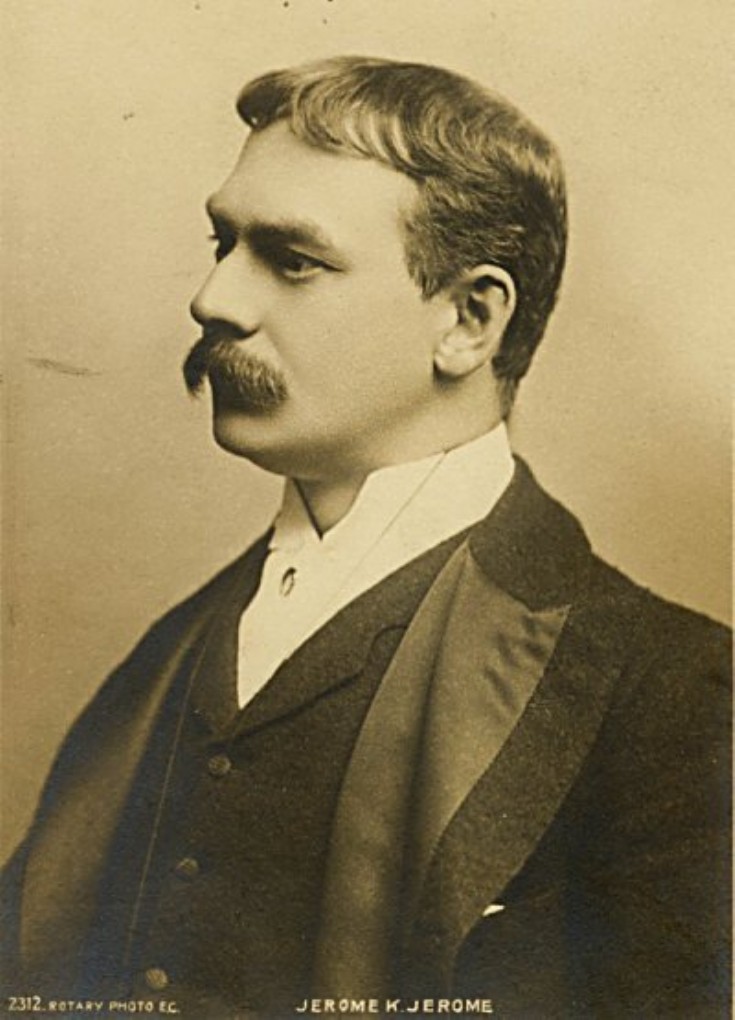

Jerome K. Jerome's 1893 tale of cabin fever. For a legendary humorist JKJ had a fine way with weird, disturbing fiction. We're in the Alps again, this time for a folk tale. The narrative device is the familiar one of someone - a nice, sensible chap, of course - discovering some writings in an old building.

Stephen Gallagher's tale of travellers stranded in a workmen's hut by a British motorway features - yet again - a female spirit drifting through the blizzard, luring men to their doom. This one is distinctly more violent than those Victorian/Edwardian ghosts, as befits a modern horror tale. And here the vengeful ghost has a solid motive, in marked contrast to Blackwood's nature spirit.

4. 'The Winter Ghosts'

This short 2009 novel by Kate Mosse begins with over references to Blackwood and M.R. James. Set in the French Pyrenees, it concerns an Englishman whose car goes off the road in a blizzard. He makes his way to a nearby village and is invited to take part in a traditional feast. It emerges that the distant past - that of the brutal suppression of the Cathars - is not dead and gone.

5. 'The Captain of the Pole-Star'

We're back to the realm of mysterious, scary, but fascinating female spirits for this one by Arthur Conan Doyle. The doctor of a whaling ship in the Arctic offers an account of a strange cry heard from the pack ice, and of the ghost some of the whalers claim they saw. The captain is clearly obsessed with the eerie spirit, even though it means risking his life, and those of his men...

1. 'The Glamour of the Snow'

Algernon Blackwood's 1912 tale of a somewhat reclusive, sensitive Englishman on holiday in Switzerland. He feels estranged from his countrymen and women, but finds a sympathetic skating partner on the rink at midnight. The mysterious female companion entrances him, until eventually he is lured out of the town and up into the Alps...

2. 'The Woman of the Saeter'

Jerome K. Jerome's 1893 tale of cabin fever. For a legendary humorist JKJ had a fine way with weird, disturbing fiction. We're in the Alps again, this time for a folk tale. The narrative device is the familiar one of someone - a nice, sensible chap, of course - discovering some writings in an old building.

At home I should have forgotten such a tale an hour after I had heard it, but these mountain fastnesses seem strangely fit to be the last stronghold of the supernatural. The woman haunts me already. At night instead of working, I find myself listening for her tapping at the door; and yesterday an incident occurred that makes me fear for my own common sense.3. 'The Horn'

Stephen Gallagher's tale of travellers stranded in a workmen's hut by a British motorway features - yet again - a female spirit drifting through the blizzard, luring men to their doom. This one is distinctly more violent than those Victorian/Edwardian ghosts, as befits a modern horror tale. And here the vengeful ghost has a solid motive, in marked contrast to Blackwood's nature spirit.

4. 'The Winter Ghosts'

This short 2009 novel by Kate Mosse begins with over references to Blackwood and M.R. James. Set in the French Pyrenees, it concerns an Englishman whose car goes off the road in a blizzard. He makes his way to a nearby village and is invited to take part in a traditional feast. It emerges that the distant past - that of the brutal suppression of the Cathars - is not dead and gone.

5. 'The Captain of the Pole-Star'

We're back to the realm of mysterious, scary, but fascinating female spirits for this one by Arthur Conan Doyle. The doctor of a whaling ship in the Arctic offers an account of a strange cry heard from the pack ice, and of the ghost some of the whalers claim they saw. The captain is clearly obsessed with the eerie spirit, even though it means risking his life, and those of his men...

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

THE WATER BELLS by Charles Wilkinson (Egaeus Press, 2025)

I received a review copy of The Water Bells from the author. This new collection contains one tale from ST 59, 'Fire and Stick'...

-

This is a running review of the book Spirits of the Dead. Find out more here . My opinion on the penultimate story in this collection has...

-

'B. Catling, R.A. (1948-2022) was born in London. He was a poet, sculptor, filmmaker, performance artist, painter, and writer. He held...

-

The 59th issue of the long-running magazine offers a wide range of stories by British and American authors. From an anecdote told in a Yorks...