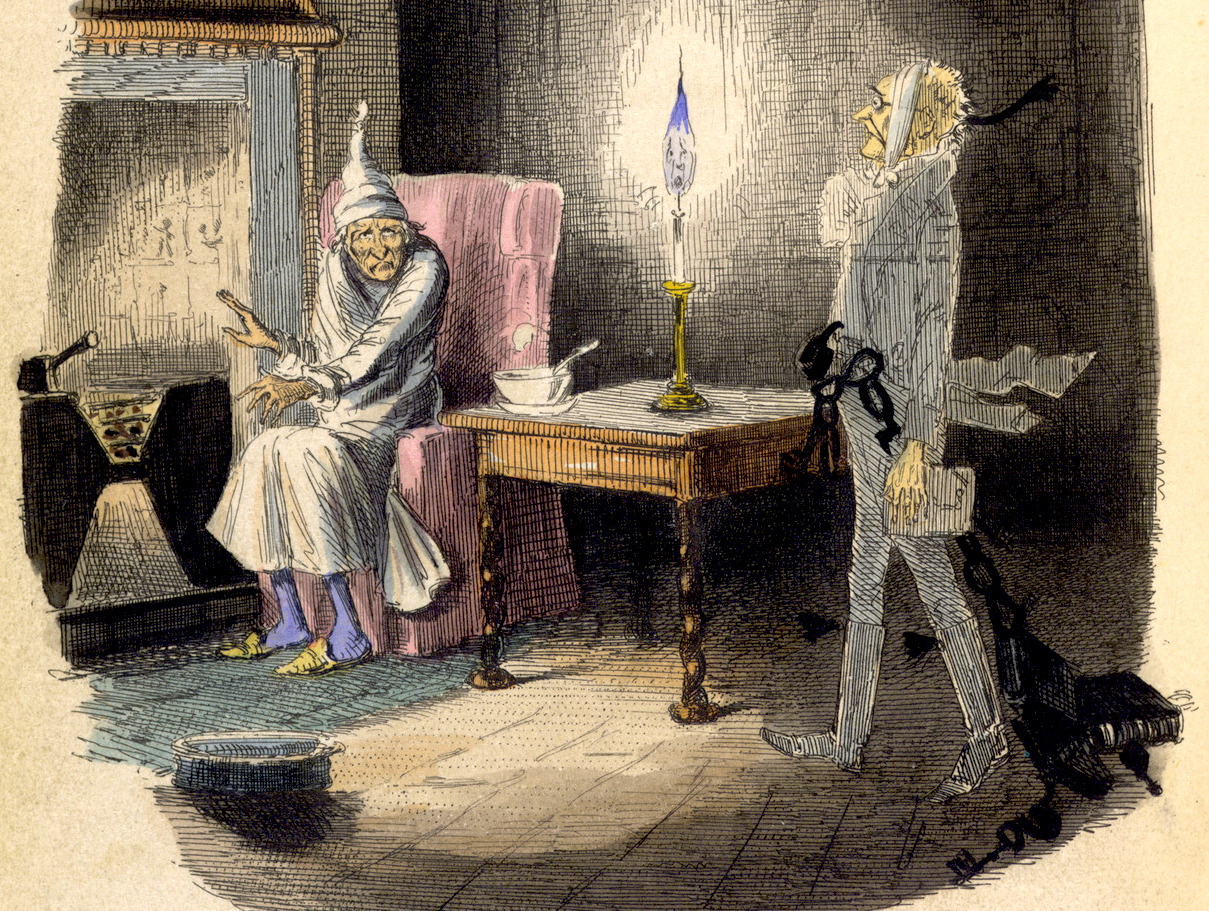

The story, 'The Devil of Christmas', concerns Krampus, the satanic being who supposedly comes to whisk away unruly children in the Austrian Tyrol. Of course it's just a silly story. But why does the picture of Krampus on the chalet wall have such compelling eyes...? And who is responsible for strange nocturnal antics that terrify the British visitors' young son?

In the hands of Shearsmith and Pemberton this could have been a rather nifty supernatural comedy-drama, But instead it's something altogether stranger, as after a couple of minutes a voice over begins, and we are in the realms of DVD commentary. The director of 'The Devil of Christmas, played by Derek Jacobi, asks for the tape to be rewound so we can see a minor continuity error. We see unedited footage, and its explained that the leading man is speeding up his dialogue to get things over with because he had another job that day.

This layered approach is great fun, and paradoxically enough makes the story we have been told is a piece of old hokum even more interesting. The script and acting are pitch perfect, and the presence of Rula Lenska as the boy's stroppy, glamorous gran is a nice touch. ('Missed her mark, poor love.') A lot of cliches are carefully re-used, particularly the twist ending that so often fell flat. The final twist here, which I didn't expect, puts everything we've just seen in a new light. This certainly bodes well for the all-too-few episodes to come next year.