I enjoyed this little documentary, not least because of the sympathetic and intelligent tone taken by the presenter, Professor Ronald Hutton. Some genuinely interesting revelations, too, not least Churchill's late-blooming sympathy for Spiritualism that led to the repeal of the Witchcraft Act.

Sunday, 28 July 2013

Wiccan's World

I enjoyed this little documentary, not least because of the sympathetic and intelligent tone taken by the presenter, Professor Ronald Hutton. Some genuinely interesting revelations, too, not least Churchill's late-blooming sympathy for Spiritualism that led to the repeal of the Witchcraft Act.

ST#24 looms, a bit

Due to various minor glitches the latest issue of ST will be a week or two late - it will definitely be out next month, though. And it's worth waiting for! Here's a sneakety-sneak preview of the cover pic, which is by Sam Dawson.

Saturday, 27 July 2013

Walden East

Over to the right - just along and down a bit from this - there's a Link List. This is a list of links. Oh yes. And I sometimes forget to point you over there so you can see what interesting things other people are doing on the intertrons. Among the newer editions is Walden East, the site of writer, reviewer, and all round good egg John Howard.

Walden East consists of essays on authors and themes, plus some content. There's splendid stuff about Fritz Leiber, for instance, and even some poems of the fantastic in House of Moonlight. Oh, and there are lots of reviews. All in all, it's a feast for the mind, especially when John tackles some of the more esoteric ideas found in Machen's work. And I can't resist ending with this Machen quote:

Walden East consists of essays on authors and themes, plus some content. There's splendid stuff about Fritz Leiber, for instance, and even some poems of the fantastic in House of Moonlight. Oh, and there are lots of reviews. All in all, it's a feast for the mind, especially when John tackles some of the more esoteric ideas found in Machen's work. And I can't resist ending with this Machen quote:

Yes, for me the answer comes with the one word, Ecstasy. If ecstasy be present, then I say there is fine literature; if it be absent, then, in spite of all the cleverness, all the talents, all the workmanship and observation and dexterity you may show me, then, I think, we have a product (possibly a very interesting one) which is not fine literature.

Thursday, 25 July 2013

The Night Alive

A friend of mine who happened to be in London last weekend decided to go and see Conor McPherson's new play at the Donmar Warehouse. My friend then emailed myself and other like-minded folk that:

this is a bit of a departure from McPherson’s norm. It’s a comedy with some very graphic violence. The violence drew a loud gasp from the audience as it was so unexpected and a couple of children were led out in some distress. I won’t spoil it for anyone who is going to see it, but there is a very small “spooky bit” but you have to concentrate on the text to spot it.As a minor aside, I'm surprised that children were allowed in by the Donmar. There are more reviews, of course, and a good summary of the critical response here. As a McPherson fan I'd like to see 'The Night Alive', but since this one stars Ciaran Hinds and is directed by the author I suspect it will not go on tour. Ah well. Such is life in the provinces.

Wednesday, 24 July 2013

Xothic Sathlattae

Cardinal Cox, indefatigable bard of the weird, has produced a pamphlet of poems that combines the style of Fitzgerald's Rubaiyat with Lovecraftian lore. Here's the press release, which you can click to enlarge:

As always, the Cardinal demonstrates a firm grasp of the poetic tradition he's adorning/subverting by putting a strange spin on it. This is a glimpse of the nicely-produced pamphlet itself.

Like the Rubaiyat, the poem tells a story replete with imagery, as the nameless protagonist ventures into a 'cursed empty quarter' and encounters strange creatures. Djinns and ghouls are well-represented, along with the less familiar shockers such as supposedly extinct 'lizard-people'. (Does David Icke know about this?) There are also fish-folk 'like men, yet scaled', who recall the Babylonian Oannes. Great fun and as erudite as ever, this is a fine addition to the Cox Canon.

Monday, 22 July 2013

A Chimaera in my Wardrobe

Tina Rath's stories about the small, amiable chimaera that is indeed found in a wardrobe started appearing in Supernatural Tales in 2002. Issue #4 saw the eponymous title story of the series, in which the chimaera tells an impoverished bit-part actress ('Supporting Artiste', or SA) a series of tall stories. But none, of course, are as unlikely as the storyteller himself. More stories duly appeared, the last in 2009's ST#16 ('Trouble with the Hob'), but not all of the chimaera's tales fitted the ST format - some were more science fiction than supernatural, for instance. But they're all very enjoyable and written with consummate elegance, and you can buy them all now as an eBook for Kindle.

The thing that I admire most about Tina Rath's work is the way she combines a keen intelligence with understated wit. She easily weaves werewolves, vampires, ghosts and less likely creatures into her tales, while always keeping the reader's feet on the ground with her command of detail and deft characterisation. This is especially true in her 'double act' stories featuring two police officers - Sgt Prendergast and PC Oliver. The former is older, fatter, and considerably wilier than the young, idealistic constable, and provides many of the book's best lines.

If you're looking for a pleasant, stimulating read, with humour and a hint of melancholy (after all, the chimaera only stays for a summer), then this is a book for you. And I believe a hardback collection may be in the offing for those who shun the fell engines of the digital revolution!

The thing that I admire most about Tina Rath's work is the way she combines a keen intelligence with understated wit. She easily weaves werewolves, vampires, ghosts and less likely creatures into her tales, while always keeping the reader's feet on the ground with her command of detail and deft characterisation. This is especially true in her 'double act' stories featuring two police officers - Sgt Prendergast and PC Oliver. The former is older, fatter, and considerably wilier than the young, idealistic constable, and provides many of the book's best lines.

If you're looking for a pleasant, stimulating read, with humour and a hint of melancholy (after all, the chimaera only stays for a summer), then this is a book for you. And I believe a hardback collection may be in the offing for those who shun the fell engines of the digital revolution!

Tuesday, 16 July 2013

The Double

This is a guest post by James Everington.

There are, appropriately enough, two different types of story about doubles, about doppelgangers.

The first type is probably best exemplified by The Body Snatchers by Jack Finney. The doubles are the famous ‘pod-people’ – not actually people at all, their resemblance to those they copy only skin-deep. A scary and a brilliant metaphor for paranoia and the enemy-within, but largely an external threat.

An example of the second is The Double by Jose Saramago. In this story, the central character (with the singular name, ha ha, of Tertuliano Maximo Afonso) sees an actor in a film who looks exactly like him... or exactly like he did five years ago, when the film was made. Further investigation of other films the actor has been in shows that throughout their lives the two men have always looked identical – the resemblance even including such things as both of them growing a moustache at the same time. The threat posed to Tertuliano by his double is not physical, but existential – he becomes preoccupied about who out of the two of them was born first; who was the original and who the copy. He tracks his double down, and eventually they meet and… well, that would be telling.

Saramago’s style might initially seem off putting – he writes in long sections with very few paragraph breaks, even for conversations between two characters. There are digressions, playful postmodern asides, and a 'character’ called ‘common sense’ who Tertuliano gets into long, bickering arguments with before he does something stupid. It's like a short story by Borges expanded to novel-length by Beckett’s repetition and detours, with a dash of Monty Python.

But, once the prose gets under your skin (and the translator must take some credit for this) you find it has a rhythm and a beat all of its own. It becomes a pleasure to read and there’s some genuinely funny moments. But this lightness of touch doesn’t quite disguise the creepy nature of the tale Saramago is telling. It’s like someone determinedly laughing and joking when they tell you of some bad experience they’ve had - it doesn’t quite ring true and the fact they are smiling as they tell you makes it all the more unnerving. Tertuliano’s double is still out there.

Towards the end of the book the pace picks up, as the consequences of Tertuliano's meeting his double play out – there’s some surprises and a certain tragic inevitability about events, before a final twist that even the second time reading the book I didn’t spot coming (in my defence it was years after I first read it).

There’s more than a few doubles in my stories in Falling Over, and both the title story and New Boy were deliberate attempts to deal with the theme. In both, the doppelgangers appear to be external ones like Finney’s body snatchers, but I also wanted the central characters to experience some of the existential unease and uncertainty of Tertuliano Maximo Afonso. In a sense, they both move from the first type of double story to the second.

The Double is a truly remarkable book, one that some people out there appear to hate. Whether this is to do with Saramago’s writing style or something else I’m not certain. From my perspective all I can say is I think those people are missing something great, a book and an author truly like no other (Saramago won the Nobel Prize in 1998). I don’t think his is a name who is mentioned in terms of horror fiction very often and indeed any connection must be considered tangential. But in the same way that the term ‘weird fiction’ can be stretched to include Kafka, it can be stretched some more to include Saramago.

-------

Falling Over is published by Infinity Plus and is out now. Ten stories of unease, fear and the weird.

"Good writing gives off fumes, the sort that induce dark visions, and Everington’s elegant, sophisticated prose is a potent brew. Imbibe at your own risk." - Robert Dunbar, author of The Pines and Martyrs & Monsters.

Find out more at Scattershot Writing.

There are, appropriately enough, two different types of story about doubles, about doppelgangers.

The first type is probably best exemplified by The Body Snatchers by Jack Finney. The doubles are the famous ‘pod-people’ – not actually people at all, their resemblance to those they copy only skin-deep. A scary and a brilliant metaphor for paranoia and the enemy-within, but largely an external threat.

An example of the second is The Double by Jose Saramago. In this story, the central character (with the singular name, ha ha, of Tertuliano Maximo Afonso) sees an actor in a film who looks exactly like him... or exactly like he did five years ago, when the film was made. Further investigation of other films the actor has been in shows that throughout their lives the two men have always looked identical – the resemblance even including such things as both of them growing a moustache at the same time. The threat posed to Tertuliano by his double is not physical, but existential – he becomes preoccupied about who out of the two of them was born first; who was the original and who the copy. He tracks his double down, and eventually they meet and… well, that would be telling.

Saramago’s style might initially seem off putting – he writes in long sections with very few paragraph breaks, even for conversations between two characters. There are digressions, playful postmodern asides, and a 'character’ called ‘common sense’ who Tertuliano gets into long, bickering arguments with before he does something stupid. It's like a short story by Borges expanded to novel-length by Beckett’s repetition and detours, with a dash of Monty Python.

But, once the prose gets under your skin (and the translator must take some credit for this) you find it has a rhythm and a beat all of its own. It becomes a pleasure to read and there’s some genuinely funny moments. But this lightness of touch doesn’t quite disguise the creepy nature of the tale Saramago is telling. It’s like someone determinedly laughing and joking when they tell you of some bad experience they’ve had - it doesn’t quite ring true and the fact they are smiling as they tell you makes it all the more unnerving. Tertuliano’s double is still out there.

Towards the end of the book the pace picks up, as the consequences of Tertuliano's meeting his double play out – there’s some surprises and a certain tragic inevitability about events, before a final twist that even the second time reading the book I didn’t spot coming (in my defence it was years after I first read it).

There’s more than a few doubles in my stories in Falling Over, and both the title story and New Boy were deliberate attempts to deal with the theme. In both, the doppelgangers appear to be external ones like Finney’s body snatchers, but I also wanted the central characters to experience some of the existential unease and uncertainty of Tertuliano Maximo Afonso. In a sense, they both move from the first type of double story to the second.

The Double is a truly remarkable book, one that some people out there appear to hate. Whether this is to do with Saramago’s writing style or something else I’m not certain. From my perspective all I can say is I think those people are missing something great, a book and an author truly like no other (Saramago won the Nobel Prize in 1998). I don’t think his is a name who is mentioned in terms of horror fiction very often and indeed any connection must be considered tangential. But in the same way that the term ‘weird fiction’ can be stretched to include Kafka, it can be stretched some more to include Saramago.

-------

Falling Over is published by Infinity Plus and is out now. Ten stories of unease, fear and the weird.

"Good writing gives off fumes, the sort that induce dark visions, and Everington’s elegant, sophisticated prose is a potent brew. Imbibe at your own risk." - Robert Dunbar, author of The Pines and Martyrs & Monsters.

Find out more at Scattershot Writing.

Thursday, 11 July 2013

The Curse of Casterbridge

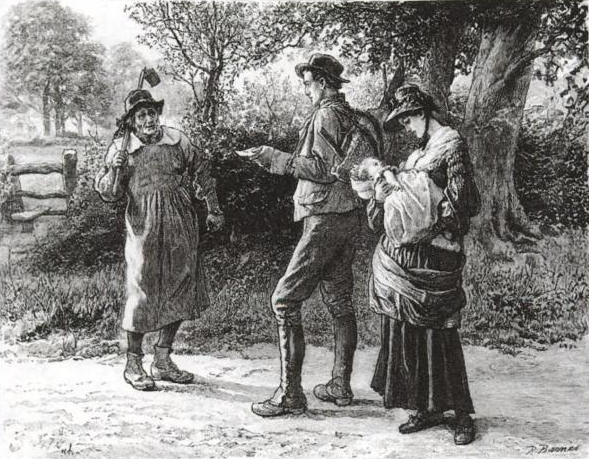

|

| On the way to the fayre |

I enjoy a good radio drama, and it so happens that Radio 4 Extra offers a veritable feast of classics, novelties, obscurities, and generally good stuff. There's always a dramatisation of a classic novel to be heard, and this week I've been immersed in The Mayor Casterbridge.

This is of course one of those Thomas Hardy Wessex novels that pits a flawed man against fate and shows exactly how tragic an apparently ordinary life can be. The eponymous mayor, Michael Henchard. When he's young, drunk, and impecunious he sells his wife to sailor at a fayre. His wife, Susan, is willing to go because Henchard is a bad-tempered, self-pitying pain in the arse. She takes their infant daughter, Elizabeth-Jane, with her. Such wife-selling was not unheard of in Hardy's youth.

When Henchard sobers up he is stricken by remorse and resolves never to touch drink for twenty-one years - his age at the time of his 'crime'. He journeys to Casterbridge (Dorchester), earns a reputation as a sober, hard-working man, and eventually rises to become a leading corn factor, magistrate, and mayor. Enter Susan and Elizabeth-Jane, who arrive in Casterbridge searching for news of the sailor - who has apparently been lost at sea. Enter also Donald Farfrae, a young Scot set on emigration who has modern ideas about agriculture and who, having offered Henchard some free advice, is offered a job as his business manager.

Rather than summarise the novel, let's just say that complications ensue when Henchard is confronted by his wife and daughter, and the latter becomes enamoured of Farfrae. Henchard becomes jealous of Fafrae for no good reason, and his resentment leads to disaster. This path of destruction is marked by two examples of Henchard's drawing on supernatural forces (so he thinks) to thwart his rival.

Saturday, 6 July 2013

Written by Daylight - Review

Written by Daylight is the first collection of John Howard's stories published by Swan River Press. All eleven tales in WbD are republished from earlier collections or anthologies, but it so happens that all were new to me. As always with The Swan River Press, this is a beautifully produced volume. The cover art is striking and its imagery - an ordinary man's dreams presented as a fantastic vista - seems especially pertinent.

If there is a unifying theme here it is the transience of existence, from the individual to the social and even the geographical. In 'Westenstrand' a man sets off for an island off Germany's North Sea coast during the last months of the Weimar Republic. The island is constantly being reshaped by tide and storm, so that no map can ever be wholly reliable. The protagonist journeys to Westenstrand to try and rekindle a relationship but comes to realise that 'we both understood that the map had changed'.

Changing maps also inform 'Into an Empire', in which a Londoner obsessed with the collapsed empires of old Europe - Russia, Germany, and Austria-Hungary - collects their coins, notes, and stamps. His behaviour grows more pointlessly regimented, like the regimes that fascinate him, until he undergoes a personal collapse which might also be an epiphany.

Another fine story, 'Time and the City', recalls the British New Wave science fiction of the early Seventies. It might have been penned by J.G. Ballard, Christopher Priest, or Brian Aldiss. It's the tale of a dream-project in which a man is put into a kind of controlled trance so as to visualise an Atlantis-like civilization. It contains some of the best writing in the book, perhaps because John Howard feels more comfortable on the margins of sf. At one point descriptions of 'immense mechanisms' recalled Forbidden Planet, and the story does indeed culminate in the realisation of dreams, albeit in a very different way.

Exiles, migrants (internal and external), loners, and misfits populate these pages. Few find what they are searching for, and indeed they seldom can be sure what it is. Thus in ''Where Once I Did My Love Beguile'' a boy's friendship with an old man reveals a lost love, and causes a strange maybe-miracle that is also a personal tragedy. This one threw me precisely because I expected one character to be the focus of some strange event, whereas in fact a mysterious event occurs in the life of the other. Sort of. To be honest, I'm not sure, but it is a compelling and gently-handled denouement.

'The Way of the Sun' strays close to a comedy of manners, as an Englishman sets out (during what I assume to be the post-war era) to drive the length of Italy along the as-yet unfinished Autostrada del Sole. Along the way shy, sensitive James encounters a British couple who seem to be swingers. Ironically it is through them that he realises his ambition to find 'the balcony of the Mediterranean' in Lamolfo, but they also make it impossible for him to enjoy it. There's a touch of Alan Bennett about it all, but also a sense that James will never be able to make the personal journey he longs for, and will always fall victim to the unwanted attentions of more crass individuals.

'Silver on Green' is different again, but still focuses on the themes of loss, failure, and the possible escape by visionary means from worldly disasters. Here an exiled statesman from a Balkan kingdom sliding towards fascism (I at once thought of Romania and its Iron Guard) beguiles his time in a London suburb by collecting coins of his homeland. The conclusion is deftly handled, but it did seem a little forced to me. Or perhaps it is an argument in favour of a political quietism that I am not willing to accept?

The same can't be said for 'Winter's Traces', in which a writer sets out to discover something about an obscure composer of light music. William Winter, it transpires, was unable to create during the last years of his life because his genius was, in a sense, appropriated by the city he loved, the London of the railway and the Tube. The striking central idea is a poetic one, worthy of Blackwood or Machen, while the description of the composer's idyllic surburban life adds a Betjemanesque touch that I found charming.

In marked contrast is 'A Gift for the Emperor', set in East Prussia just before the outbreak of the Great War. Unusually for him, in this story Howard offers us an admirably settled society - that of the old Junker aristocracy yearning for the days of Bismarck. But the Count and Countess von Stern are thrown into confusion when, instead of an expected visit from the Kaiser, they instead receive a portrait. The picture shows Wilhelm II holding a particular volume of Kipling that he enjoyed when he last graced them with his presence. The couple's confusion and near panic as they try to grasp the significance of the gift is a powerful metaphor (to me, at any rate) for the way Europe's empires slid chaotically into war in the late summer of 1914. The story is a bit of a tease, though - we are left to wonder what particular stories or poems impressed the emperor, and whether Kipling might even be in part to blame for Germany's belligerent stance.

Overall, I was impressed with WbD. One or two stories seemed to me too slight and inconclusive to stay in the mind. But most are not only well-written but also offer remarkable ideas. Reader beware, though - these are not, strictly speaking, ghost or horror stories, and those who like everything explained in the last few paragraphs will find little but frustration here.

If there is a unifying theme here it is the transience of existence, from the individual to the social and even the geographical. In 'Westenstrand' a man sets off for an island off Germany's North Sea coast during the last months of the Weimar Republic. The island is constantly being reshaped by tide and storm, so that no map can ever be wholly reliable. The protagonist journeys to Westenstrand to try and rekindle a relationship but comes to realise that 'we both understood that the map had changed'.

Changing maps also inform 'Into an Empire', in which a Londoner obsessed with the collapsed empires of old Europe - Russia, Germany, and Austria-Hungary - collects their coins, notes, and stamps. His behaviour grows more pointlessly regimented, like the regimes that fascinate him, until he undergoes a personal collapse which might also be an epiphany.

Another fine story, 'Time and the City', recalls the British New Wave science fiction of the early Seventies. It might have been penned by J.G. Ballard, Christopher Priest, or Brian Aldiss. It's the tale of a dream-project in which a man is put into a kind of controlled trance so as to visualise an Atlantis-like civilization. It contains some of the best writing in the book, perhaps because John Howard feels more comfortable on the margins of sf. At one point descriptions of 'immense mechanisms' recalled Forbidden Planet, and the story does indeed culminate in the realisation of dreams, albeit in a very different way.

Exiles, migrants (internal and external), loners, and misfits populate these pages. Few find what they are searching for, and indeed they seldom can be sure what it is. Thus in ''Where Once I Did My Love Beguile'' a boy's friendship with an old man reveals a lost love, and causes a strange maybe-miracle that is also a personal tragedy. This one threw me precisely because I expected one character to be the focus of some strange event, whereas in fact a mysterious event occurs in the life of the other. Sort of. To be honest, I'm not sure, but it is a compelling and gently-handled denouement.

'The Way of the Sun' strays close to a comedy of manners, as an Englishman sets out (during what I assume to be the post-war era) to drive the length of Italy along the as-yet unfinished Autostrada del Sole. Along the way shy, sensitive James encounters a British couple who seem to be swingers. Ironically it is through them that he realises his ambition to find 'the balcony of the Mediterranean' in Lamolfo, but they also make it impossible for him to enjoy it. There's a touch of Alan Bennett about it all, but also a sense that James will never be able to make the personal journey he longs for, and will always fall victim to the unwanted attentions of more crass individuals.

'Silver on Green' is different again, but still focuses on the themes of loss, failure, and the possible escape by visionary means from worldly disasters. Here an exiled statesman from a Balkan kingdom sliding towards fascism (I at once thought of Romania and its Iron Guard) beguiles his time in a London suburb by collecting coins of his homeland. The conclusion is deftly handled, but it did seem a little forced to me. Or perhaps it is an argument in favour of a political quietism that I am not willing to accept?

The same can't be said for 'Winter's Traces', in which a writer sets out to discover something about an obscure composer of light music. William Winter, it transpires, was unable to create during the last years of his life because his genius was, in a sense, appropriated by the city he loved, the London of the railway and the Tube. The striking central idea is a poetic one, worthy of Blackwood or Machen, while the description of the composer's idyllic surburban life adds a Betjemanesque touch that I found charming.

In marked contrast is 'A Gift for the Emperor', set in East Prussia just before the outbreak of the Great War. Unusually for him, in this story Howard offers us an admirably settled society - that of the old Junker aristocracy yearning for the days of Bismarck. But the Count and Countess von Stern are thrown into confusion when, instead of an expected visit from the Kaiser, they instead receive a portrait. The picture shows Wilhelm II holding a particular volume of Kipling that he enjoyed when he last graced them with his presence. The couple's confusion and near panic as they try to grasp the significance of the gift is a powerful metaphor (to me, at any rate) for the way Europe's empires slid chaotically into war in the late summer of 1914. The story is a bit of a tease, though - we are left to wonder what particular stories or poems impressed the emperor, and whether Kipling might even be in part to blame for Germany's belligerent stance.

Overall, I was impressed with WbD. One or two stories seemed to me too slight and inconclusive to stay in the mind. But most are not only well-written but also offer remarkable ideas. Reader beware, though - these are not, strictly speaking, ghost or horror stories, and those who like everything explained in the last few paragraphs will find little but frustration here.

Thursday, 4 July 2013

American Ghosts

This is the day when we commemorate American Independence, and tens of millions of English speaking people conspire to pretend that the French didn't win a war. For obvious reasons.

Anyway, it's only natural (or indeed supernatural) to ponder American ghost stories. And there sure are a lot of 'em! Many of them ladies. A lot of Ph.D time has been put into the issue of why women wrote ghost stories in the 19th century, but it's fairly obvious that crafting supernatural fiction was seen as a ladylike pastime, rather like embroidery. Which is ironic, given that a lot of those stories, read against the grain, are rather subversive.

But, rather than subject you to my unoriginal thinking, here's a chance to bridge the Atlantic with a ghost story set in little ol' England, penned by an American woman, and produced as a British TV costume drama. Hope you're keeping up!

Tuesday, 2 July 2013

Happy Days!

No, not that one. 'Happy Day' is the superficially cheery but in fact deeply weird greeting of the villagers in the Seventies kids' cult series children Children of the Stones. If you don't know it, think The Prisoner with a Gothic, time-travel twist and you're halfway there. It's about a community that no-one can leave, due to a strange (but quite well explained) connection between a 5,000 year-old stone circle and a distant black hole. It's brilliant stuff and I recommend it to anyone.

There's a very good Radio 4 documentary on the series, Happy Days: The Children of the Stones, presented by comedian Stewart Lee. And here is a glimpse of the BBC iPlayer programme notes...

There's a very good Radio 4 documentary on the series, Happy Days: The Children of the Stones, presented by comedian Stewart Lee. And here is a glimpse of the BBC iPlayer programme notes...

- Broadcast onBBC Radio 4, 1:30PM Sun, 9 Jun 2013

- Available until12:00AM Thu, 1 Jan 2099

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

THE WATER BELLS by Charles Wilkinson (Egaeus Press, 2025)

I received a review copy of The Water Bells from the author. This new collection contains one tale from ST 59, 'Fire and Stick'...

-

This is a running review of the book Spirits of the Dead. Find out more here . My opinion on the penultimate story in this collection has...

-

'B. Catling, R.A. (1948-2022) was born in London. He was a poet, sculptor, filmmaker, performance artist, painter, and writer. He held...

-

The 59th issue of the long-running magazine offers a wide range of stories by British and American authors. From an anecdote told in a Yorks...