Over at The Conversation is an interesting item on English vampires. Or, more precisely, genuine folk belief (with some official endorsement) in the undead. As we know, however, when people claim that 'vampires' exist anywhere, definitions become a bit baggy.

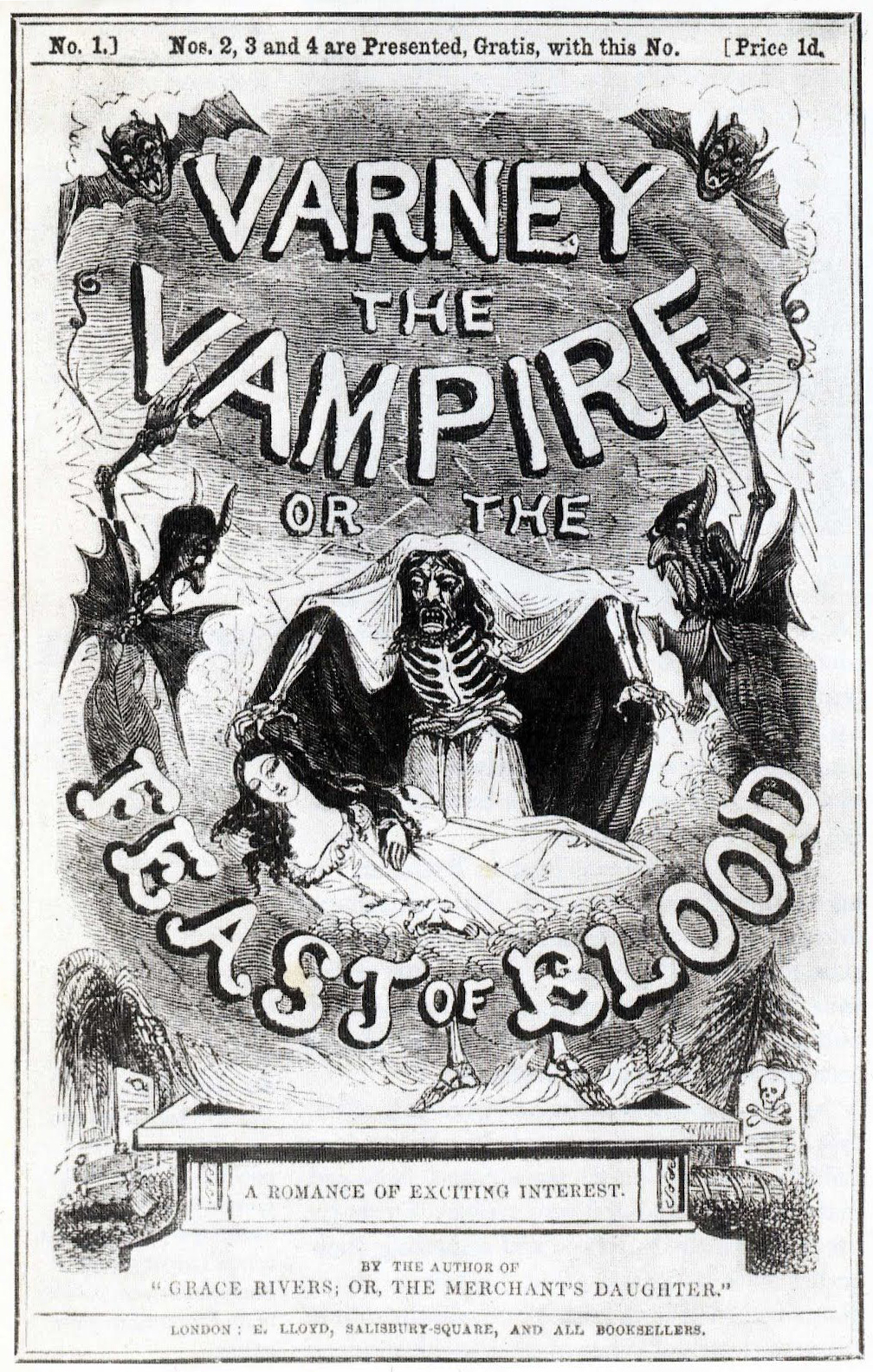

The author, literature lecturer Sam George, draws the usual link between Byron and Polidori's story 'The Vampyre'. What she does not say, unfortunately, is that this led to a string of imitative penny dreadful vampire storie, often published anonymously (as Polidori's story was, originally). Among these tales was ''Varney the Vampire: or, The Feast of Blood', serialised 1845-7.

In 1894 Augustus Hare published an account of a supposedly real vampire occurrence. The Vampire of Croglin Grange is cited in the Conversation piece, though the dates seem to differ with other accounts. And, as people have pointed out, it does read like a pastiche of earlier vampire fictions, particularly a scene in which the vampire picks the glass from a window pane to access his victim's home. Varney did exactly the same thing.

Both Varney and the Croglin Vampire stories mention a vampire forcing their way into a heroine’s bedroom by removing a small pane of glass. The vampires each release the catches on the door and wrap the girls hair around their bony fingers. Then the vampires tilt the girls neck, plunge their teeth into her; a gush of blood and a sucking noise follows.I think George is on firmer ground with the Buckinghamshire 'vampire' that was suppressed by a saint, no less. St Hugh, Bishop of Lincoln, was told the corpse in question should be dug up and burned. Instead he laid an absolution on the un-decayed corpse, which was put to rest. These medieval legends concerning saints are not remotely reliable, of course, but it's interesting to see that there was a tradition of the dead walking and praying on the living in the 12th century.

I also like the story of the Cumbrian village of Renwick, supposedly terrified by a bat-like monster that emerged from the foundations of a church at some point in the remote past. People of Renwick became known as 'Bats'. There was even a punk band called the Renwick Bats. Even more suggestive is the sheer number of broken and burnt human remains found in the deserted Yorkshire village of Wharram Percy. Some think they are evidence of cannabilism, others suggest that around 100 bodies were mutilated to stop the dead from rising.

I suppose what all this proves is that the Dracula story crystallised fictional character and folk beliefs into a very commercial form of vampire, complete with suitably exotic folklore. This eclipsed the kind of the folklore that helped inspire M.R. James, whose ghosts often seem to be radically modified versions of the deceased. The 'ghosts' in 'The Mezzotint', 'Wailing Well', 'Martin's Close' and other stories are not ethereal enough to be conventional Victorian spooks. Like Dracula, they give a bit more substance to supernatural menace.

1 comment:

"...they give a bit more substance to supernatural menace." Exactly. The most frightening ghost stories I've ever read always involved a physical aspect to the threat. I'm thinking Ghost Story by Peter Straub where some of the ghosts can hurt you physically versus Julia by the same author where one is never sure if the ghost of Olivia exists only in the title character's fragile mind and if it's the protagonist herself who is causing the mayhem (the ending doesn't make things any more clearer, at least to me).

Apparently the writer of the Langella Dracula was aware of the idea of the vampire picking the pane of glass because that scene is in the movie, although it's not as scary as what I've imagined when I came across the story of the Vampire of Croglin Grange.

Post a Comment